Modern Front End Fundamentals - Semantic HTML & Accessibility

In this series of blog posts we’re going to be looking at some of the fundamentals we need to know as modern front end developers. These fundamentals are framework agnostic, if you’re building it for the web you should have an understanding of these concepts.

To get started we’re looking at HTML (HyperText Markup Language) which is literally the foundation of the web. No matter what language or framework you’re building, it’ll all render out to HTML in the browser (unless you’re building in Flash, but that’s a completely different conversation). If we look at HTML as our foundation, we need to make sure we have a good solid foundation to our websites otherwise it’s going to make everything else that we build on top that much harder, so it’s important to start strong. It’s because of this that we’re going to look at the importance of Semantic HTML, the most solid foundation we can build.

Semantic HTML introduces meaning to the content inside an element

The way that semantic HTML introduces meaning to content is similar to how TypeScript introduces meaning to the values and functions we have inside JavaScript, by using a semantic HTML element we’re able to define the type of content we’re using, rather than it being a generic any value. We can technically use generic container elements like div and span for displaying all our content, then add a whole bunch of code on top of it to get it to look and function the way we want it to, but if we choose a semantic element instead, it’s literally built in!

<!-- Semantic Button -->

<button onclick="doSomething()">Click Me!</button>

<!-- Non-Semantic Button -->

<div class="button" id="doSomethingButton">Click Me!</div>

<script>

document.getElementById('doSomethingButton').addEventListener('click', () => {

doSomething();

});

</script>

Now not all HTML elements are semantic, some of them are just generic container elements (which is fine, they still have a place), and some are for presentational purposes only (which could also be accomplished via CSS), for example both the b and strong tags will make text bold by default in browser styling, but the strong tag will also emphasise the text for screen reader users, similarly to the way the increased font weight does for visual readers.

<!-- Presentational Element -->

<b>This text is bold</b>

<!-- Semantic Element -->

<strong>This text is bold, and screen readers will tell the user it's important</strong>

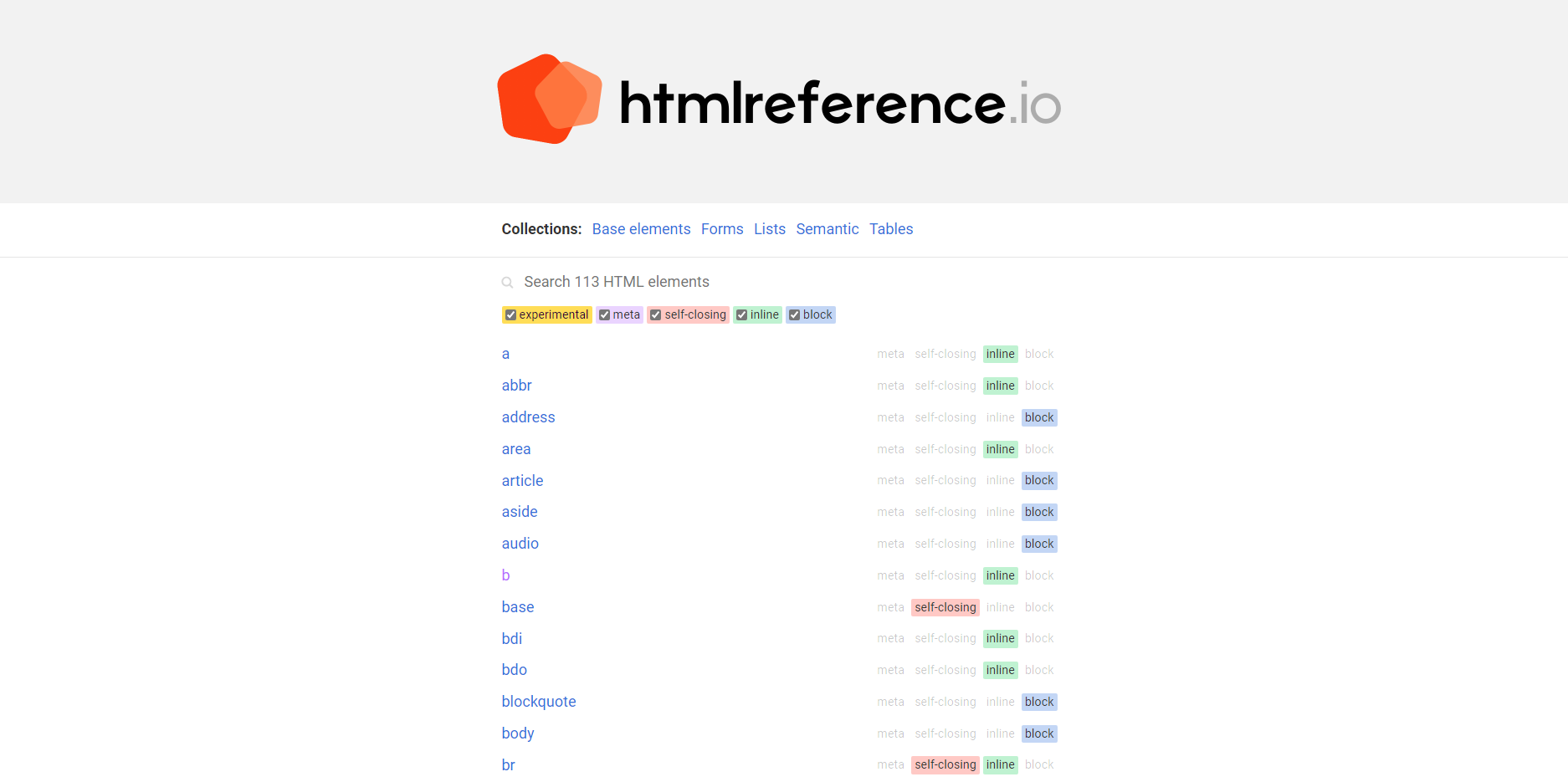

When working out which element is the right one to use, htmlreference.io is a great place to start. Using this to identify which is the best HTML element to use for our content we can make our code more semantic and accessible for everyone (and maybe reduce some of the CSS and JavaScript needs too).

Accessibility

But what’s this got to do with Accessibility you say? We’re just talking about using the right kind of HTML elements. Well the secret is that using Semantic HTML is the best first step we can take to building more accessible web experiences for everyone. Looking at the top 5 most common accessibility issues on the web, 4 of them are related to non-semantic or invalid HTML. If we were able to fix them, we could solve over 90% of all accessibility issues. That’s making the web 90% better, 90% more accessible straight out of the gate!

When I talk to people about building this with accessibility in mind, a lot of people talk about how it’s too hard to do it properly, or they don’t know how, or they don’t have budget to hire a specialist. And while I’m not saying it wouldn’t be great to have all these things and fix everything, every step we take makes things easier for everyone. Plus if you are going to get an expert in to help you out, wouldn’t you prefer they help you with the curly questions, the real problems, rather than them needing to list all of the invalid HTML first?

What does a11y have to do with Accessibility?

Before we go on, I also want to address a commonly used abbreviation used, which is A11y. This is an alphanumeric abbreviation for the word Accessibility, which is often used as a shorthand. An alphanumeric abbreviation is often used for long words where the number of characters between the first and last character (in the case of Accessibility, there are 11 letters between the A and Y) replaces those characters, ie. Accessibility becomes A11y. Another commonly used alphanumeric abbreviation is I18n which is short for Internationalisation (18 letters between I and N). So next time someone uses A11y (they may use the word verbally, pronounced as though the 1s are ls), they meaning Accessibility.

Semantic HTML and Accessibility

We’ve already talked about how semantic HTML elements introduce meaning to the content inside it, but what does that actually do? This meaning associated with each of the elements is provided to assistive technologies and they can then let the user know more about what it actually is. Maybe it’s a button or a link that can be clicked on, or a form input that needs filling in, or maybe it’s a semantic container element and it provides context to the other elements inside it, like if it’s a navigation section or maybe it’s to do with the content it contains, like a heading or an image.

With continuous updates to browser technologies, changes are there’s a HTML element to suit your needs, without necessarily needing to reach for a third party alternative or build something yourself. The time and effort that goes into releasing a new/updated HTML element to browsers, ensuring it works for everyone and with every assistive technology, native HTML elements are the best option rather than reaching for something else or rolling your own solution. And as we continue to get updates on both the elements we have and the ones we want, there are less and less reasons to not use what the browser has built in already.

Landmarks and Semantic Containers

Throughout the sites we build we’ve generally used a whole bunch of container elements to separate sections or to wrap items together, but by now you shouldn’t be surprised to know that there are semantic elements that we can use to replace some of these containers? When people use assistive technologies like screen readers, it provides an overview of the page, similar to what a sighted user does when they visually scan a page. It uses landmarks on the page to let the user know what there is, for example this page has a header, footer, navigation menu and a blog article. In the past we’ve defined these landmarks using the role attribute to assign roles to elements, eg. navigation, but for the most part they can now be replaced by semantic elements which implicitly provide this context to assistive technologies for us.

<div class="nav_menu" role="navigation">

<!-- Navigation links go here -->

</div>

<nav>

<!-- Navigation links go here -->

</nav>

By using the right semantic container elements we can more accurately break up our pages and provide context for what content is where.

ARIA

When trying to build things more accessibility, the first step is often to add ARIA attributes to all the different elements. ARIA (Accessible Rich Internet Applications) is a set of roles and attributes that the W3C (World Wide Web Consortium) defined as part of their Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) to help make the web experiences we’re building more accessible (I promise that’s the last new acronym for a while as well). This includes commonly used attributes like aria-label or role (which we just talked about), but extends to include a bunch of other states and properties that we can use, some common like aria-hidden and aria-invalid and others not commonly used like aria-flowto and aria-keyshortcuts.

Despite having access to these attributes though, they should only be used when semantic HTML doesn’t do the whole job for us (not kidding, that’s literally the first rule of ARIA).

First rule of ARIA use: If you can use a native HTML element with the semantics and behaviour already built in, instead of re-purposing an element and adding an ARIA role, state or property then do so. World Wide Web Consortium ARIA Guidelines

The most common use case I’ve found for using ARIA (other than building more complex JavaScript components) is aria-labelledby, allows us to provide an accessible name for an element by pointing it elsewhere in the DOM. This is useful for things like links and buttons that have generic text content (eg. Read more, Book Now) or are just icons without a label. This works similar to when we link a form input and it’s label using the for and id attributes, only with aria-labelledby we define the id on the labelling element (in this case the heading) and reference it on the element being labelled.

<!-- Linking a label and input using the `for` and `id` attributes -->

<label for="firstname_field">First Name</label>

<input id="firstname_field" name="first_name" />

<!-- Linking a generic or un-described link with a label -->

<h2 id="html_and_a11y">Semantic HTML and Accessibility</h2>

<p>

To get started we're looking at HTML which is literally the foundation of the web...

<a href="/HTML-and-a11y" aria-labelledby="html_and_a11y">Read more</a>

</p>

There are many things that we can do to make our websites more accessible, but every little bit helps to make the web a better place for everyone. The best thing we can do to start being accessible is using Semantic HTML, that way it’s accessible and readable by assistive technologies like screen readers and means that more people are about to consume the content we’ve built. If we don’t start with these good foundations, it makes it harder for us to build better experiences on the web. But by making an effort to use Semantic HTML and ensuring that our website is built well it makes it easier as we build more on top, as well as for the users who are navigating and using the experiences we’ve built.